Inanna’s Descent is arguably the most important tale in Inanna’s mythology, with Her descent to and ascent from the Underworld mirroring the movement of the planet Venus in the sky.

The original Sumerian myth is believed to have first been written down between 2100 and 2000BCE (4100 to 4000 years ago), but could have been passed down orally as early as 2500BCE (4500 years ago).

The later Akkadian version of the myth, titled Ishtar’s Descent, was first adapted in writing around 1800BCE (3800 years ago). However, the two stories are not exactly the same.

Here, I will discuss some of the key differences between the two stories, and how they play a role in each Goddess’ characterisation—according to my own analysis, of course! I am not a scholar nor an expert in Mesopotamian history or mythology, so please bear that in mind while reading.

Preparation for Her journey to the Underworld

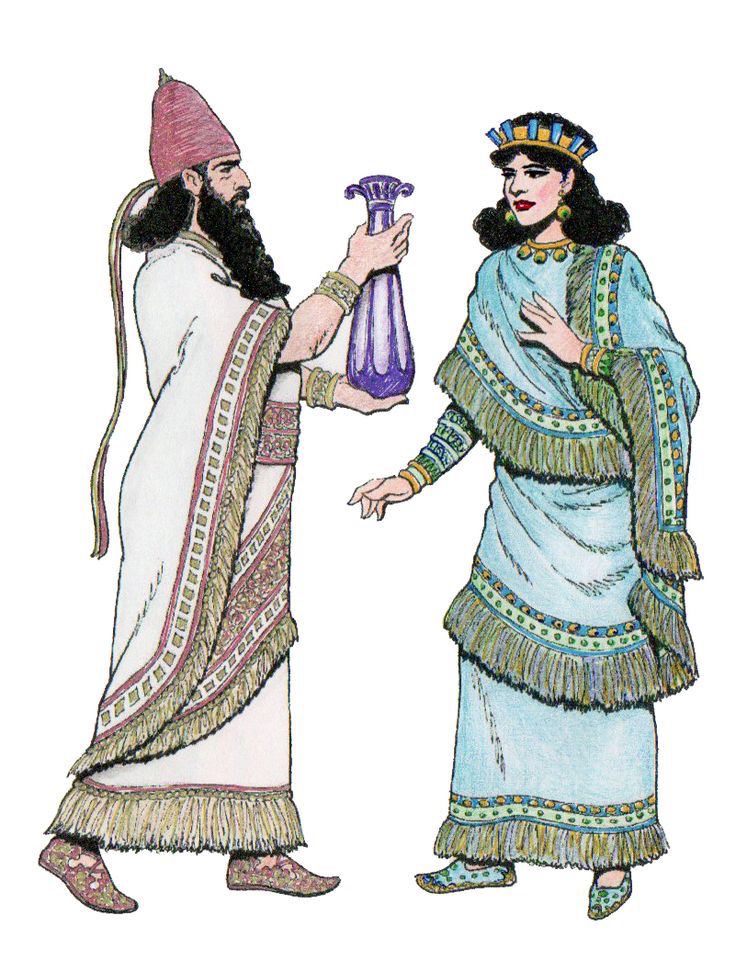

In both stories, Inanna/Ishtar prepares for Her descent to the Underworld by dressing up. Like a soldier preparing for battle, Inanna/Ishtar prepared Herself with all the items She would need in order to conquer the Underworld.

Seven items in particular are noted:

Inanna’s Descent

- “A turban, headgear for the open country,”

- ”Small lapis lazuli beads around Her neck,”

- ”Twin egg-shaped beads on Her breasts,”

- ”A pala dress, the garment of Ladyship,”

- ”The pectoral, which is named ‘Come, man, come’ over Her breast,”

- ”A gold ring on Her hand,”

- ”The lapis lazuli measuring rod and measuring line in Her hand.”

Ishtar’s Descent

- ”A large crown on Her head,”

- ”Earrings on Her ears,”

- ”Beads on Her neck,”

- ”Ornaments on Her breast,”

- “A girdle studded with birthstones around Her waist,”

- ”The anklets on Her ankles, and the bracelets on Her wrists,”

- “The loincloth on Her body.”

We can assume that the slight differences in what each Goddess chooses to wear may simply be because of the clothing conventions of each society in which each myth was written. Let’s compare each piece:

Turban vs Crown

The “turban” that Inanna wears is more accurately the shugurra, or a Sumerian headdress that represents her divinity. It is a headpiece, and using the word “turban” is more of an author’s choice than a literal wrapped cloth headdress. The removal of Her shugurra in both contexts represents a loss of Her authority and divinity.

Jewellery

In ancient Mesopotamia, lavish jewellery was reserved solely for nobility, royalty, and the Gods. Being stripped of your jewellery could represent being stripped of your high status.

In the Descent myths, this served as Inanna/Ishtar’s ritual humiliation as She descended into the Underworld and challenged Ereshkigal’s authority.

- Lapis lazuli and gold are symbols of royalty, wealth, and power, and both are sacred to Inanna/Ishtar. Relinquishing Her gold and lapis lazuli jewellery to the Gatekeeper was just like handing over a core tenet of Her personality.

- Inanna’s ring was likely a signet ring, which was worn by nobility in ancient Sumer. Signet rings were used as identification, and when pressed into wet clay they served as personal signatures. Worn, they denoted an individual’s high rank in society. Losing Her ring was not only like losing Her rank, but also Her identity.

- Additionally, the ornaments that adorned Her breasts not only beautified Her, but acted as protection. Breasts have symbolised fertility and sexuality since time immemorial, and the protection of Inanna/Ishtar’s served as protection of Her role as a Goddess of love and sex. Exposing them put them, and Her role, at risk of danger and harm.

- This thought also applies to Her girdle studded with birthstones around Her waist, and Her bracelets and anklets. The girdle, worn around Her waist, could also have been studded with protective amulets or stones meant to guarantee fertility and protect Her sacred womb.

- The lapis lazuli measuring rod and line were used as symbols of kingship and authority.

Losing all of Her jewellery not only symbolised Inanna/Ishtar’s loss of authority, but a loss of protection, identity, and Her new vulnerability as She entered the Underworld.

Clothing

Here’s a quick look at Inanna’s pala dress compared to Ishtar’s “loincloth”.

Ninshubur’s Role

In Ishtar’s Descent, Ishtar does not notify anyone of Her plan to descend to the Underworld. Inanna, however, gives Her sukkal (divine attendant) Ninshubur instructions on what to do once Inanna has descended.

”When I have arrived in the underworld, make a lament for me on the ruin mounds. Beat the drum for me in the sanctuary. Make the rounds of the houses of the gods for me. Lacerate your eyes for me, lacerate your nose for me. In private, lacerate your buttocks for me. Like a pauper, clothe yourself in a single garment and all alone set your foot in the E-kur, the house of Enlil.“

– Inana’s descent to the nether world

In case something happens to Inanna, Ninshubur must appeal to the Gods to save Her from the Underworld.

First, She is to go to Ekur and plead Her case with Enlil, the God of storms, wind, and air.

If He refuses, She is then to go to Ekishnugal and plead Her case with Nanna, the God of the moon and Inanna’s father.

Finally, if all else fails, Ninshubur is to go to Eabzu and plead Her case with Enki, the god of freshwater, wisdom, and creation. It is Enki, says Inanna, who will bring Her back to life.

Arrival in the Underworld

How each Goddess arrives in the Underworld is also different.

Inanna

When asked by the Gatekeeper why She has come to the Underworld, Inanna replies that She has simply come to pay Her respects and witness the funerary rites of Ereshkigal’s husband, Gugalanna.

Ishtar

Ishtar, on the other hand, doesn’t even give the Gatekeeper the chance to ask why She is there. She arrives at the gate and calls out to the Gatekeeper to open it; if not, she will break the door, smash the door-posts, and bring up the dead to eat the living.

Inanna, although She has come to conquer the Underworld, shrewdly uses the death of Ereshkigal’s husband as a pretext for Her visit. She attempts to conceal Her intentions under the guise of duty, acting as a Goddess who is concerned for Her sister’s wellbeing.

Ishtar, on the other hand, is much more aggressive in nature. She does not need to explain Herself to anyone, let alone a Gatekeeper. Although She doesn’t explicitly say why She has come to the Underworld, Her behaviour makes it known that She isn’t there for a quick chat and cup of tea.

Confrontation with Ereshkigal

When Inanna comes face to face with Ereshkigal, She is said to have “made Her sister Ereshkigal rise from Her throne, and instead, She sat on Her throne”. Though the text does not elaborate on how Inanna got Ereshkigal to get up, we can assume it was done cleverly.

When Ishtar comes face to face with Ereshkigal, Ereshkigal was “angered at Her presence”. Then, “Ishtar, without reflection, threw herself at her [in a rage]”. Rather than coaxing Ereshkigal off Her throne, Ishtar immediately goes on the offensive and strikes first.

Her fate

In both myths, Inanna/Ishtar is punished with death for Her transgression. Despite already being the unchallenged Queen of Heaven and Earth, She also desired to conquer the Underworld.

However, those who wish to rule the Underworld are then bound to it; they eat clay as food, drink dust as wine. If one desires to be Queen of the Underworld, She must be prepared to live as the dead do.

Another perspective is that Inanna/Ishtar descended for cultic purposes, rather than to seize the throne from Her sister. Inanna, upon giving instructions to Ninshubur, makes it clear that She has no intention of remaining in the Underworld. Maybe She wasn’t planning on taking the throne and holding onto it forever—maybe She just wanted to prove that She could.

In this sense, Her descent holds significance as a process of unprecedented vulnerability, self-discovery, and shadow work. She had already achieved Ladyship in Heaven and Earth, but Her final challenge lay beneath the surface.

For many of us, this can be equated to the past traumas or unprocessed darkness that we hold within ourselves. The journey of healing is not pleasant, nor is it something to look forward to. It is raw, it is vulnerable, and it challenges everything we believe in and hold dear.

Some people would rather that what is in the dark, stay in the dark. Some people may try to confront their innermost self, but flee when it starts to get too real, too painful.

By surrendering all of her armour and protection, Inanna/Ishtar bared Herself for the journey ahead. At each gate, She had the option to stop and return to the comfort of the surface, yet She chose to continue to the end.

Doing personal shadow work is the same. We all have the choice to abandon our journey if it gets too uncomfortable. No one likes being uncomfortable, truly. I don’t like it either. But discomfort is a signal. It shows that we are in the midst of a change, a situation where discomfort means growth. When we are challenged, we are being offered the opportunity to see things from a different perspective.

When Inanna/Ishtar was killed, it was a horrible death. Inanna was slaughtered, and Her corpse was hung on a hook for all to see. Even in death, She was humiliated.

Ishtar was afflicted with all sorts of diseases; “eye-disease against Her eyes, disease of the side against Her side, foot-disease against Her foot, heart-disease against Her heart, head-disease against Her head.” With all these diseases, we can imagine the toll it took on Her body; She would have been disfigured, and Her body ruined.

Unravelling your entire being can evoke similar feelings of death, despair, devastation, and degradation. But it is not the end—just like it wasn’t the end for Inanna/Ishtar.

Her rescue

How each Goddess was rescued from the Underworld also differs.

Inanna

As mentioned before, Inanna gave Ninshubur strict instructions on what to do once She had descended.

She made sure that lest anything happen to Her, the Gods would come to Her aid.

Thus, it is due to Ninshubur’s intervention with the Gods that Inanna was able to be returned to the realm of the living.

Ishtar

There is no mention of Ishtar telling anyone about Her intention to descend into the Underworld.

Rather, Her absence is noticed when “The bull did not mount the cow, the ass approached not the she-ass,

To the maid in the street, no man drew near

The man slept in his apartment,

The maid slept by herself.”

Instead of Ninshubur, it is Shamash, Her twin brother and God of the sun, who pleads with Ea to restore His sister to life.

Inanna does well to prepare for Her journey, leaving absolutely nothing to chance. She was aware of the peril She was about to enter, and prepared for it accordingly. It is possible that She knew that She would not be able to successfully return from the Underworld without divine assistance from the other Gods, and put Her faith in Her familial ties to Enki.

Meanwhile, Ishtar recognised that She was indispensible to both Heaven and Earth. Knowing that Her absence would disrupt the fragile balance of life, She was confident that the Gods would do everything in Their power to recover Her from the clutches of the Underworld. Ishtar put Her faith not in the Gods, but in Her own worth and value to humanity.

The alternative endings give us great insight in how to tackle our own journeys of self-realisation.

For those who typically rely on themselves and aren’t used to asking for help, Inanna’s story of completion urges us to dismantle the walls of solitude we have erected around ourselves. Being independent and self-sufficient are wonderful traits, but so is being able to ask for—and accept—help when it is needed.

For those who are too afraid to venture on their own and believe that they cannot survive outside the community that they have so painstakingly constructed, Ishtar’s story of completion encourages us to recognise our own value. Having a close-knit community that we can turn to in times of need is beautiful, but we must not let our interpersonal ties dictate our self-worth.

Sometimes, there are things that must be achieved on your own. We must be vigilant against becoming over-reliant on the strength of others, rather than on our own. You are as capable of thriving as an individual as you are within a community.

Her replacement

Finally, we can’t forget Inanna/Ishtar’s replacement in the Underworld! In both myths, it is Her consort Dumuzid/Tammuz who takes Her place.

In Inanna’s Descent, Inanna is enraged when She sees that Dumuzid has not been mourning Her death, and orders Him to be taken to the Underworld in Her stead. Dumuzid temporarily escapes with help from Utu, the sun God, before He is finally caught and banished to the Underworld.

Inanna immediately regrets Her reckless decision, and after meeting with Dumuzid’s grieving sister, Geshtinanna, a deal is made: Dumuzid will spend half of the year in the Underworld, and then Geshtinanna will complete the other half.

When Dumuzid is in the Underworld, Inanna mourns in loneliness, and the world suffers. It grows cold, and crops do not grow. However, when Dumuzid is allowed back up to Heaven, Inanna rejoices. The earth is invigorated, and life thrives. This story is better known through its Hellenic retelling, where Inanna and Dumuzid are replaced with Demeter and Persephone.

The focus of Inanna’s Descent on the cycle of life and changing of seasons reflects the ancient Sumerians’ focus on agriculture. For them, balance was a crucial part of life, as good harvests meant that they would be able to survive the harsh winters, while bad harvests meant they would starve.

In Ishtar’s Descent, there isn’t as much focus on the events leading up to Tammuz’s selection as Ishtar’s replacement in the Underworld. It mentions that His death is mourned by His sister, Belili, but there is no further indication that She would take on half of His sentence.

Rather, Ishtar’s Descent focuses on Ishtar’s commanding personality, and Her unapologetic wrath. This reflects the political landscape of the ancient Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, all of whom had empires focused on expansion, domination, and political power.

In ancient Babylonia, Ishtar was the most prominent Goddess, alongside the supreme God Marduk. In ancient Assyria, She served as the most prominent Goddess, even surpassing the national God Ashur in popularity. In these civilisations based on imperialism, it is no surprise that Ishtar’s warlike aspects were highlighted at every opportunity.

Conclusion

All in all, the differences between Inanna’s Descent and Ishtar’s Descent not only help us understand the cultural complexities of the early Sumerian and Akkadian people, but also how we can invoke the Goddess in our own journeys of spiritual enlightenment and self-realisation.

Regardless of whether you resonate with Inanna’s or Ishtar’s story more, both offer us valuable insights. I wish you all the best in your own journeys of healing and pursuits of wisdom.

May Inanna bless you all.

Last edited: August 11, 2025

Further reading

Archive, I. S. T. (n.d.). DESCENT OF THE GODDESS ISHTAR INTO THE LOWER WORLD. Internet Sacred Text Archive. https://sacred-texts.com/ane/ishtar.htm

CDLI: Wiki. (n.d.). The Descent of Ishtar to the Netherworld. https://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=descent_ishtar_netherworld

Cooper, P. G. (2021). Inana’s Descent. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/inanas-descent

Harris, R. (1991). Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites. History of Religions, 30(3), 261–278. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062957

Kramer, S. N. (1951). “Inanna’s Descent to the Nether World” Continued and Revised. Second Part: Revised Edition of “Inanna’s Descent to the Nether World.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1359570

Pryke, L. (n.d.). Friday essay: the legend of Ishtar, first goddess of love and war. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-the-legend-of-ishtar-first-goddess-of-love-and-war-78468

The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. (n.d.). Inana’s descent to the nether world: translation. https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm

Leave a comment